How Acoustic Tagging Works

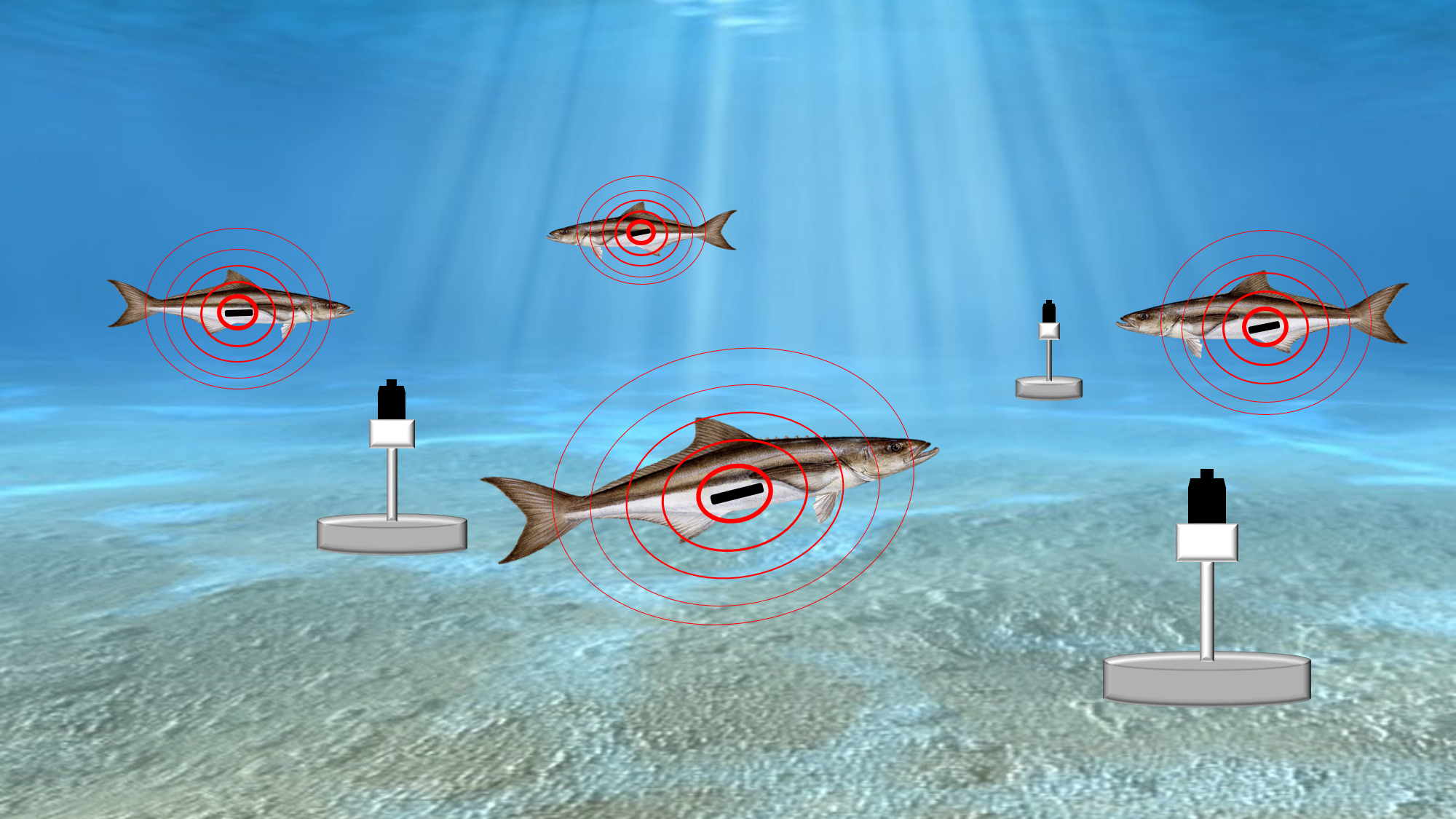

For studies focused on fish movement, acoustic tags (or transmitters) are typically surgically implanted into the abdomen of the fish. The size of the tag varies depending on the species of interest to avoid altering the animal’s behavior and ensure survivorship. Once implanted, the acoustic tags emit short pulses of sound that communicate a unique identifier at preset intervals. These ‘pings’ are detected by a nearby hydrophone, or acoustic receiver, that stores the detection data so it can be downloaded and analyzed by the researcher.

When researchers design acoustic telemetry studies, careful consideration and planning must occur to ensure that receivers are strategically located to detect fish in all areas of interest. Acoustic tags continue to ping until no battery power remains, so there is potential for animals to move great distances from their initial tagging location before the tag dies. The acoustic tag will remain in the fish for its entire life, but we will no longer receive location information once the battery is too weak to transmit. Acoustic telemetry networks allow researchers to collaborate and communicate detections of other researchers’ tags as they download their telemetry data. These telemetry networks, such as iTAG (Integrated Tracking of Animals in the Gulf of Mexico), essentially integrate the acoustic arrays of all users, which may allow for tag detections significant distances away from where the animal was first tagged, increasing our knowledge base.