Section 2 Background

2.1 Importance of data

Data are critical to making informed policies and decisions about how we manage behaviors and actions that affect the environment. As a fundamental part of the scientific method, data provide the raw information to support hypotheses that inform our understanding of natural processes. Data are the foundation for environmental research which develops this understanding and ultimately support informed decisions for managing natural resources by the TBEP. As methods for managing environmental resources continue to evolve, so does our understanding of data and its potential applications.

When we discuss “data” we often describe a very general term that has different meanings for different people. In its simplest form, data can be tabular information for the results of an experimental analysis or field survey. For environmental managers, data can mean the long-term record of routinely collected and updated monitoring information used to assess status and trends of a natural resource. Even further, data can be highly aggregated and novel products created through complex meta-analyses of independent datasets. In all cases, the need to describe a dataset’s purpose and origin, and identify its permanent and long-term home are critical to ensure forward progress in both conventional research and how research informs environmental management.

This Data Management Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) describes TBEP’s approach to address data management needs for the long-term restoration and protection of natural resources in Tampa Bay and its watershed. We are inclusive of multiple definitions of data from simple spreadsheets to more complicated workflows that generate reporting products to support environmental decisions. This broad net is designed to account for both the variety of data we use as a Program and the diversity of partner agencies we depend on to achieve our science-based mission. The management of environmental resources combines a healthy mix of conventional science with consensus driven decisions, often with strong regulatory overtones. A robust approach for working with data that promotes trust and validity in the environmental decision and ensures that science continues to progress without reinventing the wheel is foundational for these processes.

2.2 Why we need to effectively manage data

There are many reasons why data may not be effectively managed, chief among which is that it can be tedious and unglamorous work that is often an afterthought. However, investing time upfront to manage a dataset can have long term benefits, although these values may not be obvious or realized in the short-term. Lack of effective data management often results in “orphaned” datasets and data products which have lost critical reference documentation.

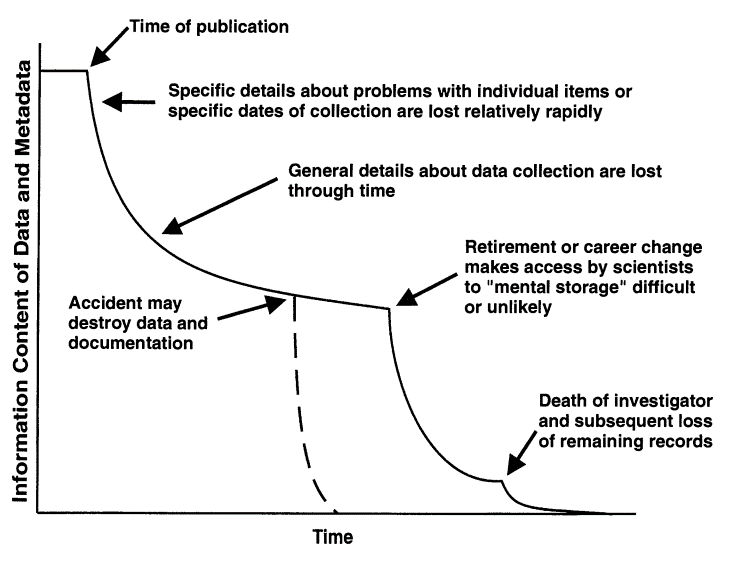

A classic graphic in Michener et al. (Michener et al. 1997) demonstrates how knowledge of a data product can be lost over time (Figure 2.1). As a research team publishes a paper, the information content of the data and metadata is at an all-time high because the ideas and concepts have been intensely studied and evaluated in the months leading up to publication. After publication, researchers move on to other projects or responsibilities, and specific details about the initial project are lost rapidly as attention is focused elsewhere. At longer time scales, other factors can contribute to the erosion of information content, including career changes through retirement or staff turnover or accidental loss of information (laptop takes a bath, lab fires, etc.).

Figure 2.1: Loss of information over time in the absence of data management (from Michener et al., 1997).

The final step in Figure 2.1 leading to absolute and complete loss of information on a data product is death of an investigator. Although a bit morbid, this is a very real and preventable problem in the process of discovery that can lead you down the frustrating path of reconstructing a data product’s origin by scouring historical records that have little to no descriptive information. As a remedy, many research teams have adopted the “bus factor” term as motivation to prevent this problem. The bus factor is an informal measurement of the relative risk associated with loss of information if an investigator was to, hypothetically, be hit by a bus (alternatively, the “lottery factor” describes departure of an individual if they were to win the lottery). Datasets or workflows that have a high bus/lottery factor are at high risk of being orphaned with the departure of a team member.

The costs of not effectively managing your data can vary, but each is a byproduct of neglecting an investment in data curation. In fact, you can probably recall several past instances when poor data management has come back to haunt you. Here are a few real-world examples:

- A collaborator calls you on the phone asking about a historical dataset from an old report. You spend several hours tracking down this information because you don’t know where it is. The data you eventually find and provide to your collaborator has no documentation and they don’t know how to use it or use it inappropriately.

- You receive a deliverable from a project partner that was stipulated in a scope of work. This deliverable comes in multiple formats with no reproducible workflow to recreate the datasets. You are unable to verify the information, eroding your faith in the final product and making it impossible to update the results in the future.

- An annual reporting product requires using new data each year. The staff member in charge of this report spends several days gathering the new data and combining it with the historical data. Other projects are on hold until this report is updated. Stakeholders that use this report to make decisions do not trust or misunderstand the product because the steps for its creation are opaque.

A more general problem with poor data management is stifled creativity. The use of other people’s data and services [i.e., “OPEDAS”; Mons (2018)] to generate novel research or data products is increasingly common, particularly in the last several decades with the advance of internet communications. Entire disciplines and new analytical methods have been developed around this idea [e.g., meta-analysis; Carpenter et al. (2009); Lortie (2014)]. The generation of new data with an incomplete history or that lack metadata documentation is a disservice to both the researcher that created the data and the larger scientific community that could benefit from further advancing this information. As a result, scientific progress will not continue as rapidly as it could if data products are discoverable and openly available.

Poor data management can also lead to peculiar or entrenched workflows that are not scalable or translatable for other users. Data managers often have their own preferences for processes that simply “work for us”, either because they were learned out of necessity because the work had to be done or it has been done a certain way for so long that it now seems normal, despite being inefficient or prone to error. In extreme cases, this can lead to workflows that may seem legitimate on the surface but are problematic because they lack a common formality or standard.

Mons (2018) describes “professorware” as a workflow to handle or generate data that addresses a novel intellectual challenge, which is important in research or discovery, but is not scalable or sustainable in the long run. Think of a pet project where you’ve written some code to achieve a certain task. It might be clunky, but you’re proud of it because it gets the job done on your computer and saves you from having to do a task by hand. These workflows often masquerade as novel “software packages” that do great things, which they can and often do, but they lack support because they’re not developed using community standards or best practices for long-term use or scalability. This is especially problematic when these workflows are intentionally or unintentionally embedded into larger data management systems. If one piece of the system lacks provenance or support, it puts the larger data management system at risk.

In summary, poor data management practices can lead to the following:

- Less collaboration in the research community

- Increased siloing among management institutions

- Less creative approaches to managing environmental resources

- Inefficient and error prone workflows that are neither scalable nor sustainable

2.3 Open Science

The open science approach provides a philosophy and set of tools to help address the costs of poor data management. Before we proceed, we need to make a distinction between the broader concept of open science and open data as one component of the former. Many of the guidelines and examples in this SOP fall broadly under the open science umbrella (or cake as you’ll see in section 4.1.1), but it’s important to understand how data management includes a set of tools that are part of, but not exhaustive of, the entire open science toolbox. Conversely, many broadly applicable open science tools that can be applied to other management scenarios can also benefit data management.

An example may be helpful. Metadata, a key component of data management, leads to more open sharing. When we talk about metadata, the assumption is that its creation is to promote sharing and transparency for open data. However, while metadata can be created in an open environment and is often created for the purpose of facilitating openness, it can also be created completely in isolation with a closed workflow, resulting in a significant potential for loss of important information.

On the other hand, broader open science principles that support a culture of sharing can also have value for research workflows that generally have nothing to do with data. For example, the “public school of thought” for open science focuses on making science more accessible to the general public, e.g., through citizen science initiatives or science blogging (Fecher and Friesike 2014). Although this approach doesn’t deal explicitly with best practices for data management, this mentality certainly has benefit for creating a culture that appreciates and learns from science, which logically leads to discussions on the importance of data.

For these reasons, this document covers many topics that may fall squarely under the realm of data management, while at other times advocating for more general open science principles with the intent of supporting a culture of better data management.

2.4 The TBEP philosophy

The Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP) is one of 28 National Estuary Programs designated by Congress to restore and protect “estuaries of national significance.” Many of these estuaries are heavily urban (i.e., having economic, recreational, cultural importance) and have had historical or ongoing issues contributing to poor environmental quality. The recovery of Tampa Bay is an exceptional story of an urban estuary that demonstrates the value of the NEP approach to restoring and protecting environmental resources. Through a coordinated regional effort of environmental professionals, utility operators, community members, and local politicians, nutrient loads to the bay have been reduced by ~2⁄3 from 1970s levels and seagrasses surpassed the 1950s benchmark extent in 2014 (Greening et al. 2014; Sherwood et al. 2017). Even more remarkable is that while the human population in the Tampa Bay watershed continues to increase, nutrient loads into the Bay remain low.

The TBEP is a key facilitator among the many local partners that have an interest in the region’s natural resources. Our facilitation is guided by several documents, including an Interlocal Agreement with our partners, a Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan, and a Strategic Plan. In simple terms, these documents respectively describe who we work with, what we need to accomplish, and how it can be accomplished.

Open science and data management have everything to do with how we facilitate bay management. Our recent update to the Strategic Plan specifically speaks to our use of open science as: 1) a general direction for how we accomplish our work to achieve the desired future state of Tampa Bay, and 2) a unique value proposition that TBEP offers within its sphere of influence. We articulate the use of open science at TBEP as a cornerstone strategy:

Be the primary source of trusted, unbiased, and actionable science for the Tampa Bay estuary, recognizing that open science principles will serve the Program’s core values.

As a Program with a small staff, successful protection of Tampa Bay’s natural resources depends on the work of our many partners. While we use open science principles internally, we can have a much greater impact if our partners understand the value of open science and actively work towards adopting its principles in their own workflows. We are actively supporting our partners through this journey through an Open Science Subcommittee that has a goal of developing a community of practice that works and learns together to navigate the open science landscape. The Subcommittee’s roles and responsibilities document explains how we are accomplishing this goal.

Our Program rests on a strong foundation of research that guides decision-making for Tampa Bay covering three decades of science and collaboration. Although great strides have been made, we intend to continue building on those accomplishments as an organization, including enhanced data management practices guided by open science principles. The details of this approach and why we’ve adopted an open science ethos are explained more fully in section 4.1.1.

2.5 Goals and objectives of this document

The overarching goal of this document is to achieve the following:

Motivate internal staff and external partners to become stewards of their data by demonstrating the value of open data practices and providing a road map to achieving this goal.

Each section of the SOP addresses a critical topic or provides a roadmap that collectively helps us work towards achieving this goal. The sections are as follows:

- Section 3: An overview of general and specific topics that are useful to understand TBEP’s core data management tenets

- Section 4: An explanation of how TBEP manages data and a roadmap to further developing internal and external workflows

- Section 5: Examples describing specific projects and why/how data management practices were applied to each

- Section 6: Parting thoughts and words of wisdom to help you continue on your open science and data management journey

- Section 7: Definitions and resources for continued learning

The TBEP has also developed a data Quality Management Plan [QMP; Sherwood et al. (2020)]. This SOP and the QMP can be viewed as complementary documents, but they were developed to meet different needs. The goal of this SOP is described above. The goal of the QMP is to ensure the data used by TBEP for decision-making has known and documented quality and is being used appropriately. In other words, the QMP establishes an internal process for ensuring data quality conforms with federal or grant-reporting requirements, whereas this document is a generalized introduction and how-to approach for data management that can help us achieve QMP goals.

Identifying what this SOP is and what it is not can help set expectations for the use of this document. As noted above, the TBEP is a relatively small organization that interfaces directly or indirectly on many projects supported or managed primarily by our partners. Because of the diversity of projects relevant to our work, it would be inappropriate and impossible to describe a detailed step-by-step SOP that could apply to every project that has relevance to the TBEP’s mission. Therefore, the approaches and workflows we describe are meant to be generalized to many project types. Any specificity that is described relates to how to use tools that have broad applicability, e.g., developing a GitHub workflow or describing general characteristics of metadata that could apply to many data types. This distinguishes this SOP from others that may apply rigorous standards to one particular problem.

To summarize, this document is:

- An explanation of the TBEP approach to data management, including our philosophy and the existing tools we have developed; and,

- A generalized cookbook describing how to manage datasets in an open science framework, including considerations before, during, and after a project.

This document is not:

- A definitive overview of best practices for data management – there are other resources (see section 7) that cover these topics in more detail; and,

- A comprehensive list of available online services for opening data, although we certainly lean towards specific platforms that we find useful.

Finally, the intended audience for this SOP is TBEP internal staff and our external partners. In both cases, the text is written to target technical staff, although the concepts and principles are appropriate for some tasks conducted by managers or higher administrative staff. These individuals are also in a position to foster better practices for data management by creating space and time for technical staff to adopt these new workflows. Understanding the importance of the tools is important, but sufficient space must be available for these skillsets to grow through a shared community of practice. Over time, the return on investment in staff developing these skillsets will be realized.