AD-1

Continue to reduce nitrogen loading from atmospheric deposition

OBJECTIVES:

Continue to support power plant upgrades and transitions to alternate energy sources. Continue to support initiatives to reduce atmospheric nitrogen pollution from vehicles. Expand the number of air monitoring stations for atmospheric nitrogen. Support research to better understand and quantify the contribution of atmospheric deposition to stormwater runoff. Support public education about the link between air and water quality.

STATUS:

Revised Action. Formerly Action AD-1 Continue atmospheric deposition studies to better understand the relationship between air and water quality. Appended with background from former Action AD-2 Promote public and business energy conservation.

BACKGROUND:

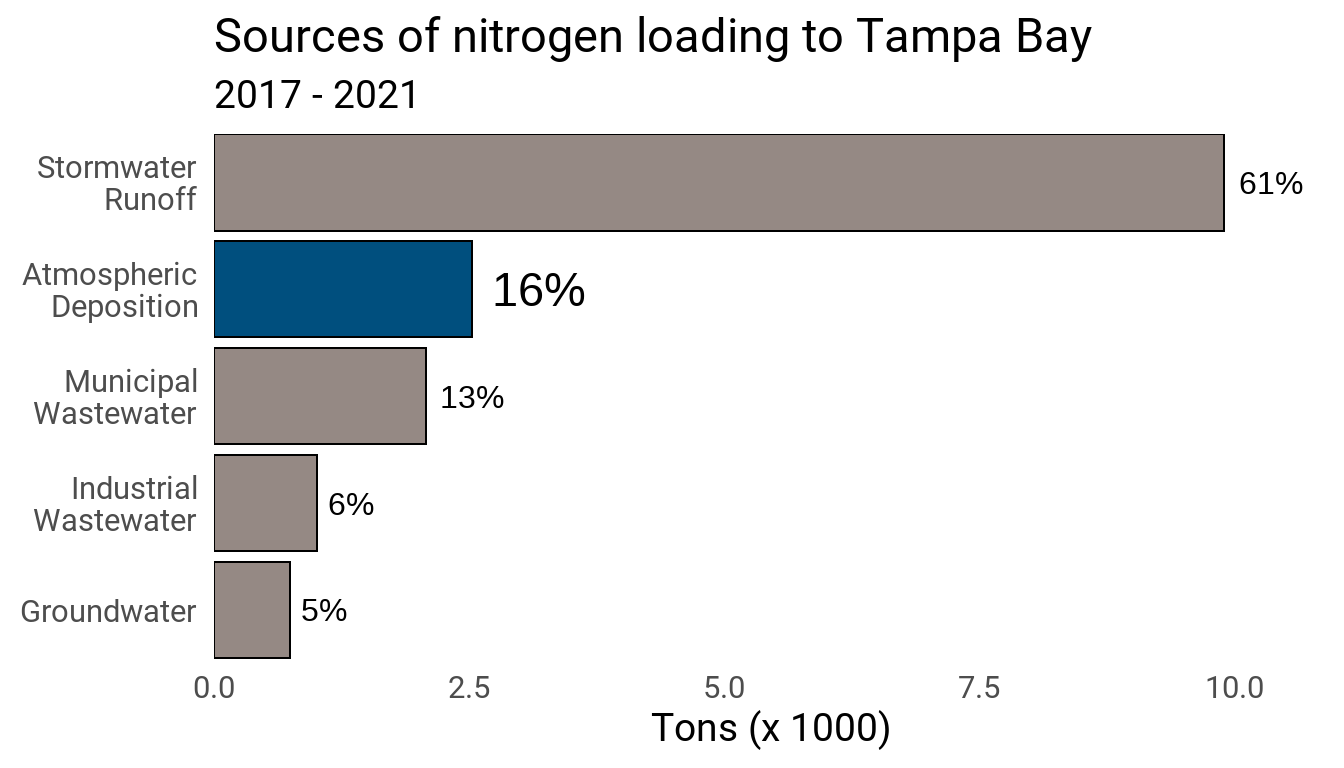

Reducing nitrogen input (loading) to Tampa Bay is a core management objective for the Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP) and its partners (see Action WQ-1). Reductions in nitrogen pollution are linked to improved water quality, recovery of seagrass meadows and associated marine life and other environmental and human health benefits.

Nitrogen (N) pollution can reach Tampa Bay from a variety of sources, including stormwater runoff from non-point sources (e.g., urban fertilizer runoff or septic systems — see Actions SW-1, SW-8, SW-10, WW-2), point sources (e.g., a wastewater treatment plant — see Actions WW-3 and WW-5), groundwater and springs and atmospheric deposition. Atmospheric nitrogen can reach bay waters directly through deposition from rainfall and dust and indirectly through stormwater runoff carrying atmospheric nitrogen deposited on impervious surfaces in the watershed.

Nitrogen can be emitted to the atmosphere from natural sources, such as manure emissions, forest fires and lightning. In Tampa Bay’s highly urbanized watershed, natural sources are a relatively small contributor to atmospheric nitrogen loading. Most atmospheric nitrogen is emitted from fossil-fuel burning power plants and vehicles.

TBEP has been a national leader in investigating and quantifying the significant role of airborne nitrogen in overall nitrogen inputs to the bay. The long-term, multi-site bay Region Atmospheric Chemistry Experiment (BRACE), completed in 2013, was conducted by scientists from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), University of South Florida, TBEP and other federal, state and local environmental agencies.

BRACE demonstrated that atmospheric deposition (both directly on the bay’s surface, and indirectly, through stormwater runoff) accounted for 57% of the total annual nitrogen loading to the bay from all sources. This contribution is mainly in the form of nitrogen oxides (NOx), which contribute to ozone, an air pollutant of public health concern in Florida. BRACE showed that atmospheric sources contributed four times as much nitrogen to Tampa Bay as discharges from municipal sewage treatment plants and industry combined.

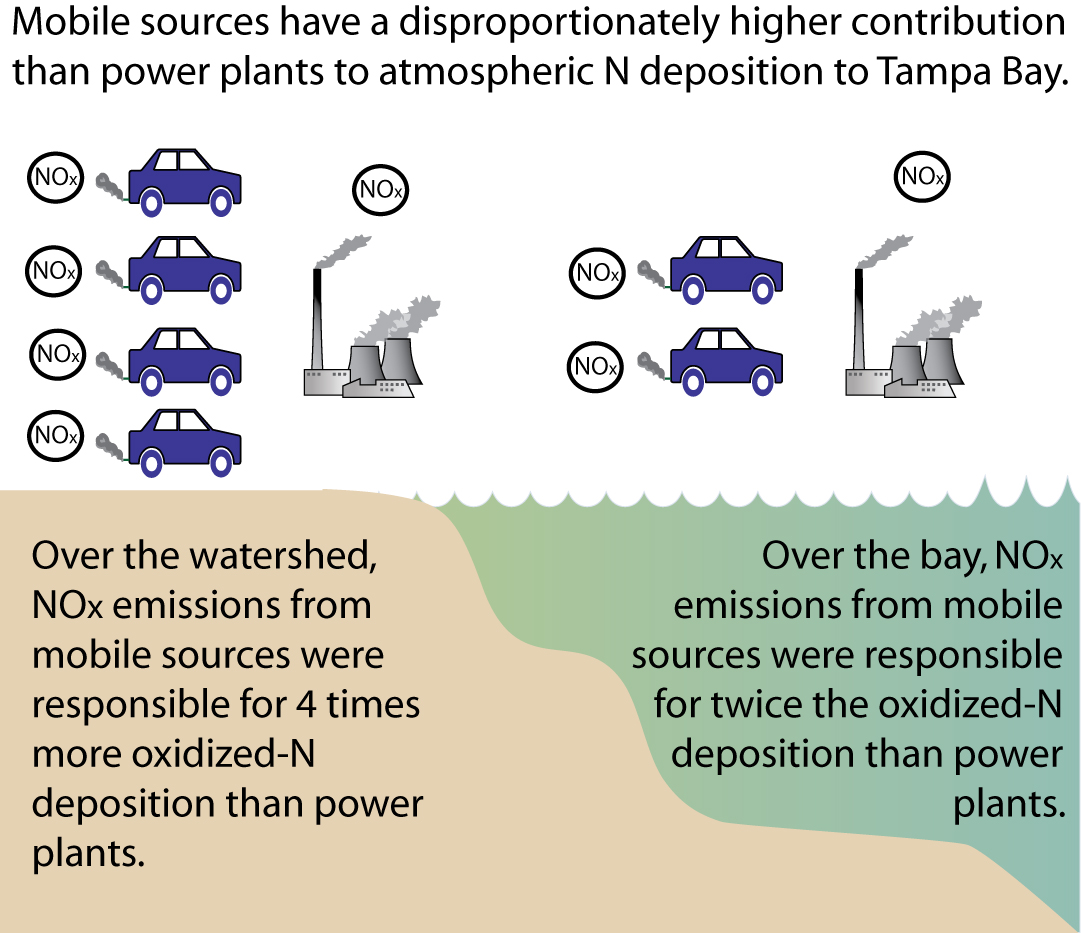

Although the bulk of emissions generated in the Tampa Bay Area originated from power plants and industry, BRACE demonstrated that emissions from vehicles had a larger local impact. This is likely due to the fact that these emissions are generated low to the ground and tend to stay within the bay watershed, while pollution emitted from tall industrial stacks is dispersed over a much larger airshed that extends north to Atlanta and south to Cuba.

Data collected for BRACE showed that, compared to power plants, vehicles contributed four times more NOx deposition to the Tampa Bay watershed and two times more NOx deposition directly to the bay. The study also reported that two-thirds of atmospheric nitrogen deposition was contained in dust particles (dry deposition) and one-third came with rainfall (wet deposition); and that air pollution from outside the Tampa Bay Area can impact the bay as well.

An ongoing University of Florida research and IFAS/Extension project aims to better understand and publicly communicate the contribution of atmospheric deposition to N loads in stormwater. The study looks at the potential impact of atmospherically derived N on water quality in the Tampa Bay watershed as it interacts with the urban tree canopy and urban impervious surfaces. Further, researchers are studying how atmospheric N may be utilized by Karenia brevis and Pyrodinium bahamense, the toxic microalgae most responsible for algal problems in Tampa Bay.

Local and national regulations are significantly reducing nitrogen emissions and improving air quality in the Tampa Bay Area.

The Cross-State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR) finalized in 2011 by the EPA requires states to improve air quality by reducing power plant emissions that contribute to fine particle pollution and ground-level ozone in downwind states. This rule replaced EPA’s 2005 Clean Air Interstate Rule. Local power plant upgrades, including replacing coal-burning plants with natural gas facilities and installing nitrogen reduction equipment on smoke stacks, resulted in a 95-ton per year decline in nitrogen emissions between 2002 and 2012.

Tampa Electric Company (TECO) replaced its coal-fired Gannon plant at Port Sutton in 2003 with the H.L. Culbreath Bayside Power Station, a 1,800 megawatt natural gas plant. According to TECO, the switch from coal to natural gas reduced nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide emissions by 99 percent and particulate matter emissions by 93 percent from 1998 levels. TECO also reported that NOx emissions from the 1,700 megawatt, coal-fired Big Bend Power Station in Apollo Beach declined 91 percent from 1998 emission levels by using technology that converts NOx into N\(_2\) and water. In 2004, TECO reduced emissions of particulate matter by 87 percent over 1998 levels by optimizing emission control units. In addition, more than $23 million in scrubber upgrades have resulted in a 94 percent reduction of sulfur dioxide levels compared to 1998 levels.

Duke Energy (formerly Progress Energy) converted its Bartow Power Plant at Weedon Island in 2009 from fuel oil to natural gas, reducing emissions by more than 80 percent, including a 98 percent reduction of sulfur dioxide emissions.

Since 2001, Florida Power and Light (FPL) has transitioned from burning more oil than any other utility in the nation to having less than 0.1 percent of its electricity generation produced from oil. Locally, FPL added a new natural gas-fueled generator at its Manatee County power plant and converted two existing units to co-fire natural gas and oil.

Both TECO and FPL began operating universal solar energy facilities in 2017. FPL’s 74.35-megawatt Manatee Solar Energy Center is among several large-scale facilities completed or planned by the company throughout Florida. The Manatee site houses 338,000 solar panels, enough to cover five football fields.

TECO launched a 23-megawatt photovoltaic (PV) array with more than 200,000 solar panels near the Big Bend Power Station. The system has the capacity to power more than 3,300 homes.

Despite its abundant sunshine throughout the year, Florida — the Sunshine State — lags nationally in solar production. In 2016, Florida voters approved a State Constitutional Amendment to provide property tax breaks for people who install solar panels on their homes.

America’s fleet of cars and trucks is becoming more energy efficient. New Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards were adopted in 2012, but are currently being reevaluated. Progress continues in developing hybrid, electric and hydrogen-powered cars. Sales of battery-powered and plug-in hybrid cars in the U.S. increased by 37% in 2016, to 159,139 vehicles. Meanwhile, the Tampa Bay Area Regional Transit Authority (TBARTA) formed in 2007 to address regional transit needs was dissolved in 2023 .

Many opportunities exist to promote energy conservation that saves consumers money and reduces NOx emissions. Examples include:

- The EPA’s voluntary Energy Star program helps businesses and individuals save money and protect the environment by identifying and promoting energy efficient products, homes and businesses. Since its inception in 1992, the Energy Star program has helped consumers save $362 billion dollars on utility bills and prevent 2.5 billion tons of greenhouse gasses.

- A variety of rebate programs, free energy audits and other incentive programs are sponsored by local utilities such as TECO, FPL and Duke Energy to increase efficiency of appliances, heat pumps, air conditioning ducts and insulation.

- UF/IFAS Extension provides a wealth of general information about energy efficiency and “living green” including specific information about energy-efficient lighting, heating, cooling and landscaping.

Despite significant reductions in nitrogen emissions from power plants and vehicles and improved energy efficiency of buildings and appliances, rapid population growth in the Tampa Bay Area may offset some of these gains. As population size and energy demand grow, continuing reductions in per capita energy use and air pollution will be needed, especially from vehicles, to maintain and improve the region’s water quality and quality of life. ( )