CC-1

Improve ability of bay habitats to adapt to a changing climate

OBJECTIVES:

Identify coastal habitats vulnerable to climate change and potential buffer areas upslope of coastal habitats. Identify methods to improve the resiliency of vulnerable bay habitats to sea level rise. Continue to investigate the carbon sequestration benefits of coastal habitats (“blue carbon”). Enhance community understanding of the potential impacts of changing climate on coastal habitats, and encourage actions to help mitigate effects.

STATUS:

New action adopted in 2014 to support ongoing and future research and restoration or mitigation of sea level rise and other projected climate change impacts on coastal habitats.

BACKGROUND:

Estuaries like Tampa Bay are particularly vulnerable to many climate change stressors, such as sea level rise (SLR), ocean acidification (see Action CC-2), warming temperatures and changes in precipitation and storm intensity. These stressors pose a variety of risks to coastal habitats.

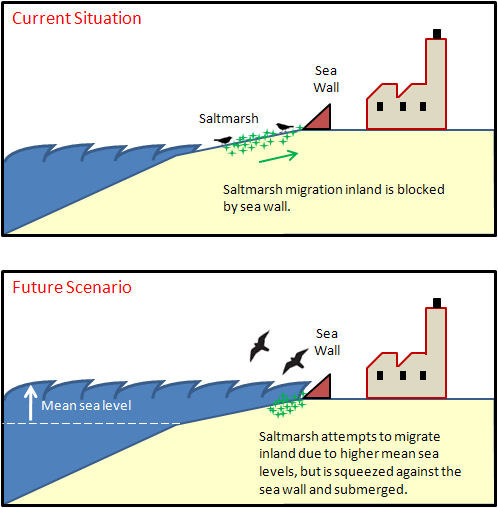

Sea level rise may increase shoreline erosion and lead to loss of beaches, salt marshes and coastal wetlands. As higher salinity waters move upslope and upstream, plant zonation will shift; where adjacent areas are developed and there is no room to migrate, coastal wetlands will become submerged. Warmer waters may promote the spread of existing or new invasive species, increased algal growth rates, decreased water clarity and low dissolved oxygen. Frequent drought or extreme flooding may alter hydrologic conditions resulting in changes to species composition and ecological function of habitats. Increased storm intensity may lead to increased nutrient pollution to the bay and shoreline erosion.

These risks to water quality, habitats, and fish and wildlife were identified in the TBEP Climate Vulnerability Analysis (2017). Risks were prioritized and climate change adaptation actions were identified in the Climate Change Action Plan (2023). Recommendations for climate risk mitigation actions, including projects and further research, were incorporated into CCMP Activities in the CCMP (2023 Interim Update).

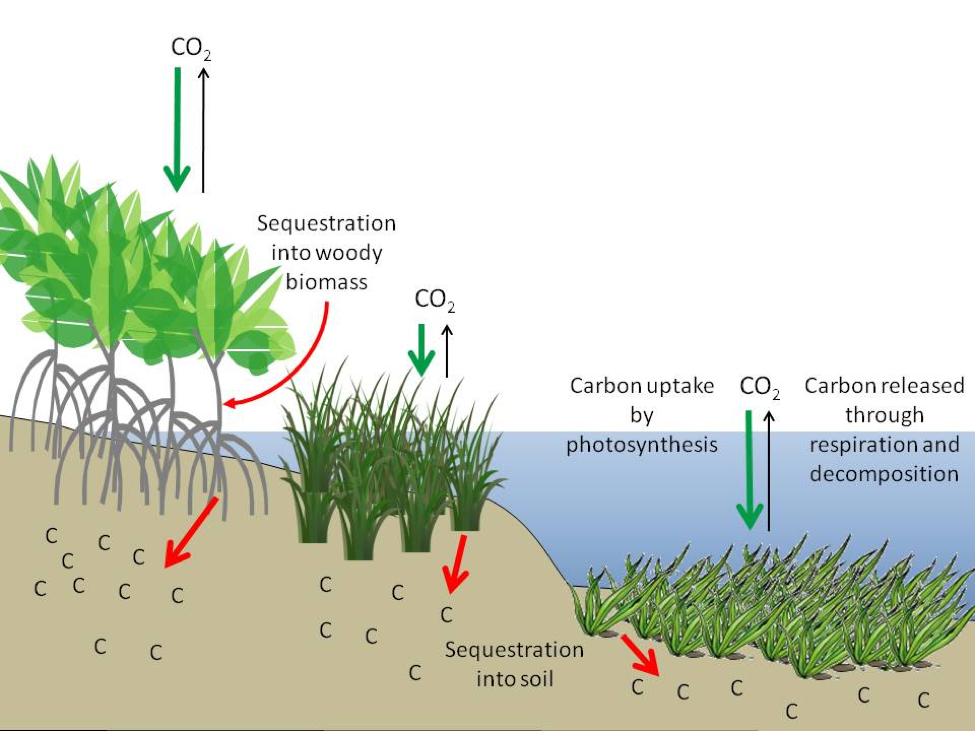

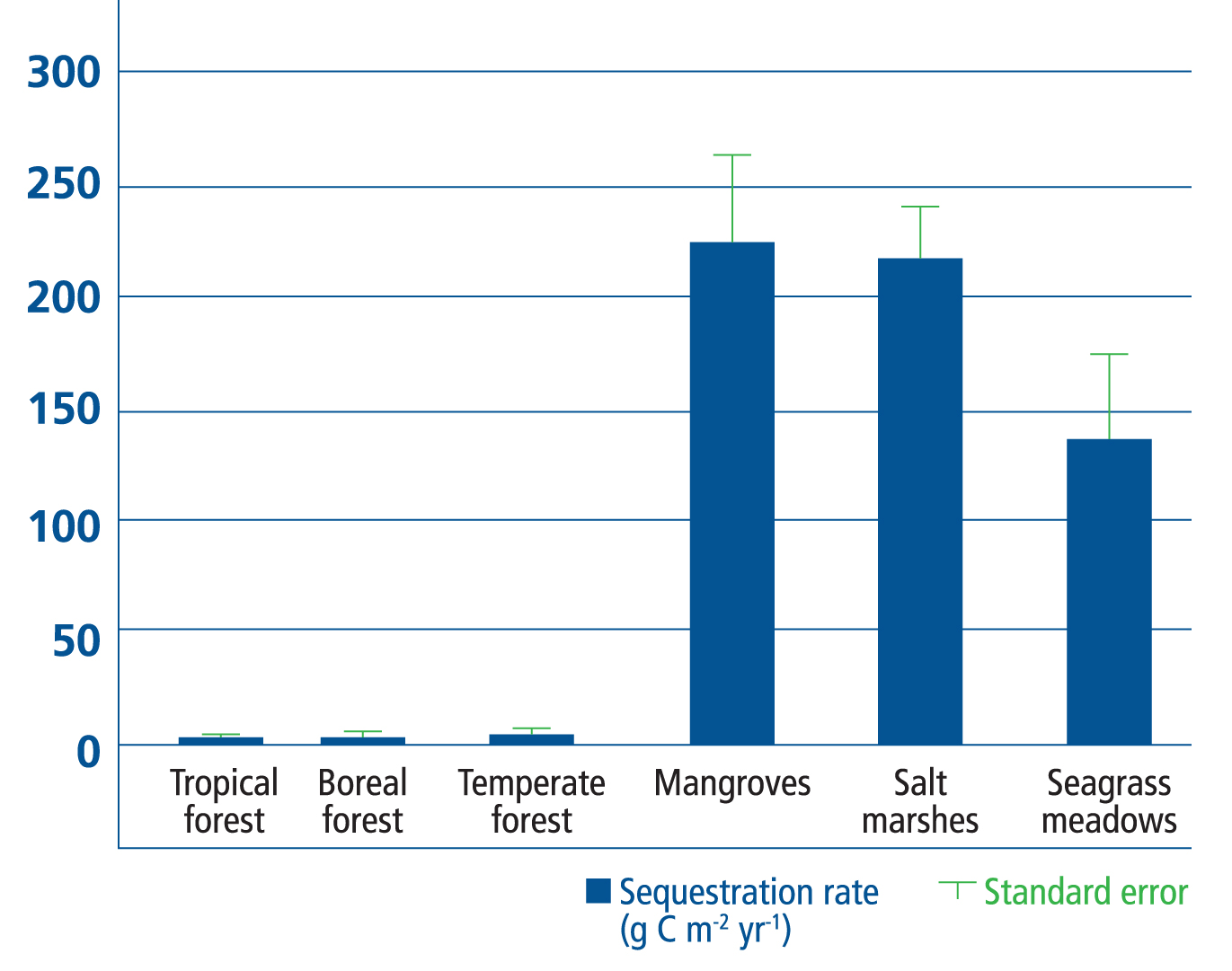

Coastal habitats are among the first to experience these impacts, but also have an important role in mitigating their effects. Tidal wetlands and seagrass habitats take up carbon dioxide and store so-called “blue carbon” in plant biomass and associated wet soils. Blue carbon ecosystems — seagrass beds, mangroves and salt marshes — store carbon at roughly 25 times the annual rate of temperate and tropical forests (McLeod et al. 2011). This is due to high primary productivity and efficiency in trapping sediments and associated carbon transported by runoff and tidal flow. In addition, seagrass beds may have a localized mitigating effect on ocean acidification (see Action CC-2).

In 2016, Restore America’s Estuaries, along with the Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP) and its partners, completed the Tampa Bay Blue Carbon Assessment to determine the climate mitigation benefits of coastal habitat restoration and conservation in Tampa Bay (Sheehan et al. 2019). The study found that Tampa coastal wetland habitats will remove over 73 million tons of CO2 from the atmosphere over the next 100 years. This is equivalent to taking 160,000 passenger cars off the road every year until 2100. The Economic Valuation of Tampa Bay (2023) values the carbon sequestration services of natural areas in the Tampa Bay watershed at $52.3 million annually (Todd, Walsh, and Neville 2023). The assessment also provides new data to help bay managers understand what actions are most needed to help mitigate the effects of sea-level rise. Potential actions include protection of upslope buffers for important habitats and species.

Hillsborough and Manatee Counties are pursuing voluntary carbon market projects to capture the value of carbon sequestration in upland habitat restoration, for example reforestation at Lower Green Swamp Preserve and Duette Preserve. Projects with blue carbon offset credits are more challenging, because the high cost of verification and monitoring requires large acreage (e.g., 1,000 acres) projects in order to realize a return on investment. Submerged lands are largely owned by the State, which has no policy mechanism for pursuing carbon credits, which could potentially help fund restoration at large scale.

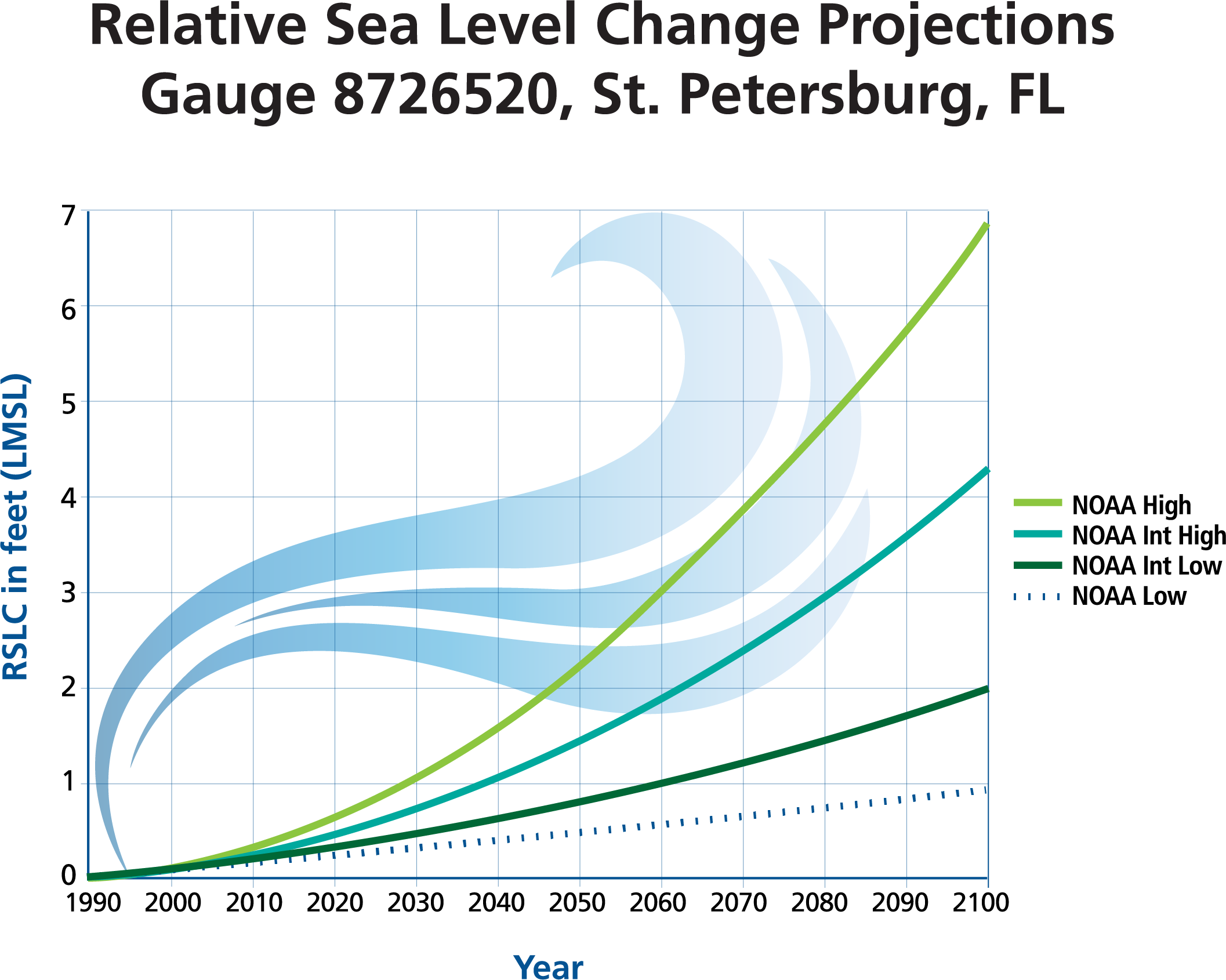

Regional projections of sea level rise for use in local planning efforts across the Tampa Bay area were updated in 2019 by the Tampa Bay Climate Science Advisory Panel (CSAP), an ad hoc network of scientists and planners working in the Tampa Bay region. The regional projections cover a set of three global sea level rise scenarios calculated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that are included in the 2018 U.S. National Climate Assessment. The projections are regionally corrected to the NOAA tide gauge in St. Petersburg and range from 0.95 to 2.56 feet in 2050 and 1.9 to 8.5 feet in 2100.

TBEP evaluated potential impacts and management implications of sea level rise on Tampa Bay’s critical coastal habitats such as mangroves, salt marshes and salt barrens (Sherwood and Greening 2014). Modeled habitat changes showed an overall loss of critical coastal habitats by 2100, with mangrove forests increasing at the expense of salt marshes and salt barrens. Protecting remaining coastal wetland ecosystems remains an important priority for TBEP (see Action BH-1).

In 2016, baseline monitoring was completed at five permanent transects throughout Tampa Bay as part of the Critical Coastal Habitat Assessment (CCHA) program. The overall goal of the long-term monitoring program is to track and assess the effects of sea level rise on the natural zonation of critical coastal habitat (i.e., mangroves, saltmarsh, salt barrens and coastal uplands) in Tampa Bay. The monitoring design seeks to collect comparable data on sites with human-related impacts, as well as other ancillary effects, such as shifts in plant or animal communities). The CCHA was expanded to five more sites in 2017, with the assistance of a Wetland Development Grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. All nine sites were monitored in 2020 and a third assessment was initiated in 2023. Future assessments at these locations will allow comparison of habitat zonation and condition over time. Preliminary observations in 2023 show that vegetation zones at Weedon Island, Fort DeSoto, and Manatee River remained the same. However, at Cockroach Bay, Harbor Palms, TECO Big Bend, and Little Manatee River, the mangrove zone expanded inland by 17-30m.

Shallow seagrass beds are vulnerable to sustained periods of elevated water temperature, which is suspected as one possible factor contributing to declines in seagrass coverage and a subsequent lack of recovery in Old Tampa Bay (see WQ-1 and WQ-3). Shallow seagrass bed temperature monitoring was initiated in 2023 in Old Tampa Bay to better understand seasonal and annual temperature trends exacerbated by changing rainfall patterns.

Establishing upslope habitat ‘refugia’ may allow coastal wetlands to persist under anticipated climate change and SLR impacts and provide new areas for recreational opportunities. Where upslope migration of coastal habitats is impeded by development, strategies such as implementing rolling easements, funding public land acquisition, requiring wetland conservation as part of new infrastructure, prohibiting construction of hardened shorelines and promoting living shorelines may be recommended (see Action BH-6). Where downstream sediment transport is necessary to protect wetlands and promote blue carbon, removal of barriers may be recommended (see Action BH-9).

Already, sea level rise is being addressed in habitat restoration projects conducted by the Southwest Florida Water Management District’s (SWFWMD) Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) program. SWIM biologists are building in space and contouring elevation so vulnerable coastal habitats can migrate upslope as water levels rise. For example, restoration of former agricultural land at Robinson Preserve’s 150-acre expansion in Manatee County will create about 85 acres of coastal upland habitats resistant to near-term sea level rise and about 55 acres of wetland and sub-tidal habitats. Efforts to restore coastal habitat mosaics that are resilient to climate change should be continued so habitats can transition, and ecosystems important to fish and wildlife can persist.

The full scope of climate change risks to the Tampa Bay Estuary is not well understood by the public; therefore, educating community members on potential impacts and actions to mitigate these impacts is an important goal of TBEP. In partnership with the Sarasota Bay Estuary Program, TBEP coordinated a photo-documentary project called “Chasing the Waves.” Local citizens were recruited to become “Tide Watchers” by taking photos of areas at low tide and at extremely high, or “king” tides, to document impacts of rising waters on structures and shorelines. While only a temporary phenomenon, king tides provide a preview of possible impacts of sea level rise when today’s high tides will become tomorrow’s low tides. Community photos were featured on a photo-sharing website, and a traveling exhibition was viewed by more than 155,000 people at county buildings, libraries and museums throughout the Tampa Bay watershed.

In 2022, TBEP partnered with the National Wildlife Federation to make a short storytelling film about climate risks and solutions called Dear Tampa Bay. The film was screened dozens of times across the Tampa Bay area and was followed up with expert-led boat tours, surveys, and focus groups. The campaign was assessed to evaluate the effect of storytelling and experiential learning on climate risk and resilience beliefs, attitudes, understanding of risk, sense of ability to act, and support for available solutions.