BH-6

Encourage habitat enhancement along altered waterfront properties

OBJECTIVES:

Expand use of living shorelines instead of traditional seawalls along waterfront properties. Support demonstration projects; explore regulatory rule revisions to support living shorelines; assess the use of living shorelines to mitigate climate change; and support education of waterfront homeowners about the benefits of living shorelines.

STATUS:

Ongoing. Revised to broaden focus on softening shorelines of privately and publicly owned waterfront properties to address coastal erosion, as a preferred alternative to coastal armoring. Action also recognizes potential for living shorelines to bolster coastal resiliency to sea level rise.

BACKGROUND:

Extensive industrial, commercial and residential development has dramatically reshaped the bay’s natural shorelines, especially in urban areas. TBEP’s first assessment of habitat losses, conducted in the early 1990s, estimated that more than half of the natural shoreline of Boca Ciega bay was altered by widespread dredging of hardened, finger-fill residential canals.

Although new “canal communities” are prohibited, the original developments remain, and vertical seawalls, revetments, riprap and bulkheads still dominate new waterfront development. Property owners in Florida are allowed to replace most existing seawalls without a permit. A 2015 report from Restore America’s Estuaries, offers mounting evidence that hardened, artificial shorelines increase erosion, harm water quality and magnify storm damage and flooding (Restore America’s Estuaries 2015). The report also notes that seawalls and other hardened shores provide poor habitat for fish and wildlife.

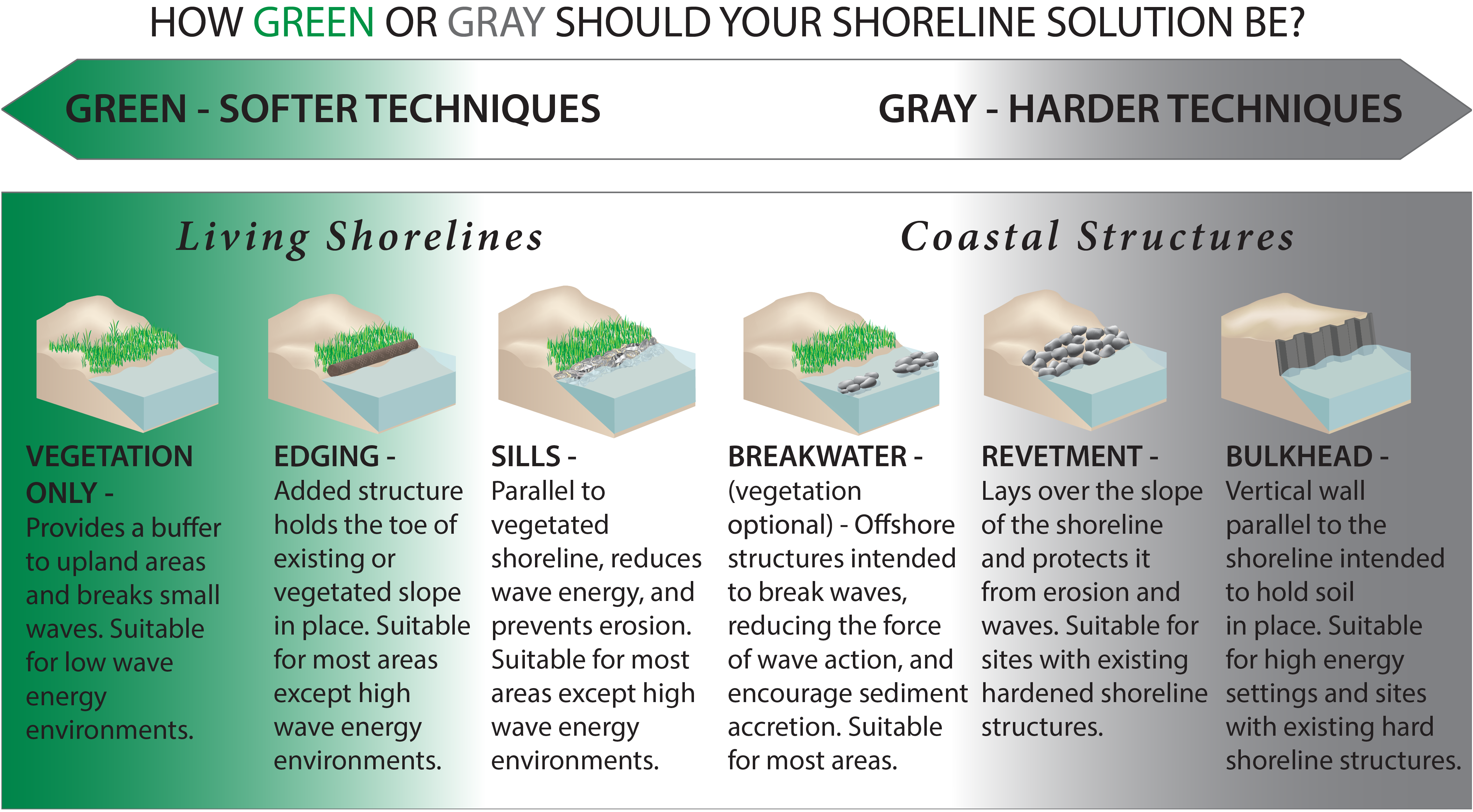

In contrast, living shorelines embrace “softer,” more natural materials that buffer wave action, absorb storm impacts, filter pollutants and provide food and shelter for fish, shellfish and wading birds. Even “living seawalls” (habitat installed in front of existing seawalls) are preferable, as these are superior to a vertical wall structure alone.

Living shorelines also help to reduce impacts associated with climate change and sea level rise by buffering the effects of increased storm and floods. They protect dunes, mangrove forests and other coastal habitats that shield manmade infrastructure and support wildlife. Case studies illustrating how coastal communities throughout the Gulf of Mexico are incorporating living shorelines into habitat restoration and protection projects to improve long-term resiliency to sea level rise are presented in the Gulf Coast Community Handbook prepared by TBEP.

Accurately defining a living shoreline is critical to widespread use and acceptance by permitting agencies and the public. NOAA describes living shorelines as “a broad term that encompasses a range of shoreline stabilization techniques along estuarine coasts, bays, sheltered coastlines and tributaries. A living shoreline has a footprint that is made up mostly of native material. It incorporates vegetation or other living, natural “soft” elements alone or in combination with some type of harder shoreline structure (e.g., oyster reefs or rock sills) for added stability. Living shorelines maintain continuity of the natural land-water interface and reduce erosion while providing habitat value and enhancing coastal resilience.”

Examples in Tampa Bay include the Ulele Spring restoration in downtown Tampa (rock revetment and native plants); the MacDill Air Force Base Living Shoreline project (oyster reefs and salt marsh grass); and the oyster reef/breakwater along the Alafia Bank Bird Sanctuary. Examples of “living seawalls” include oyster domes along downtown St. Petersburg and Tampa waterfronts.

The 2015 Restore America’s Estuaries report identifies three major barriers to widespread use of living shorelines:

- Reliance among regulators on familiar, traditional shoreline stabilization techniques, and lack of information about both the shortcomings of those methods and the benefits of living shorelines.

- Lack of a wide-angle view of shoreline management, leading to site-specific permit reviews of individual applications that overlook the cumulative effects of hardening shores and the potential values of living shorelines to mitigate habitat loss, flooding and sea level rise.

- Lack of a coordinated constituency to advocate for living shorelines.

Barriers are both institutional and educational. Creation of a living shoreline requires a permit; replacement of existing seawalls usually does not. In 2017, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers authorized a new nationwide general permit for living shorelines, making the permitting process easier. However, few waterfront property owners know about eco-friendly alternatives to hard structures. The complex permitting process, length of time it takes to obtain a permit, and the need for a qualified contractor to design and install living shorelines effectively serve as a disincentive to their acceptance and use. In locations where living shorelines alone may not be appropriate, NOAA encourages placing habitat in front of existing seawalls, a so-called living seawall. Sarasota Bay Estuary Program’s Living on the Water’s Edge brochure is an example of practical information about this topic for citizens. With support from TBERF, a Living Shoreline Suitability Model and accompanying story map were developed by FWC in 2019.

The Vertical Oyster Garden project, a partnership with Sarasota Bay Estuary Program, Manatee County and TBEP, encourages dock owners to help restore oysters by adopting strings of recycled oyster shells collected from local restaurants and hanging them off their dock. When suspended in brackish water, they provide an ideal habitat for young larval oysters to settle and grow.

Hardened structures are often necessary to protect property in areas of high wave energy and will remain a visible feature along bay and river shorelines. This action seeks to expand use of living shorelines in areas of moderate to low wave energy. The Habitat Master Plan (2020 Update) incorporates definitions and opportunities for living shorelines (Robison et al. 2020).